By LaRayne Topp

The farmers tip over a five-gallon bucket apiece, using it for a chair. Each one chooses a sandwich, heavy on the mayonnaise, and a piece of chocolate cake, iced to perfection, plus a tall tin glass of tea, the outside sweating from the ice inside. Beside them, a corn sheller stops its rumbling, resting from a half morning’s work near a pile of yellow ear corn. Wagons are heaped with shelled corn, others with corn cobs, soon to be spread out to gravel the lane or pitched into the hog pen for bedding.

The men have been up since day break, finishing chores before heading over to the neighbor’s farm where they’re part of a shelling crew. Bigger crews are reserved for threshing, but on the days they’re summoned to help shell, it will take only three or four. They’ll meet there with the man who makes his living operating a corn sheller.

At the age of 95, Wesley Schutte of Beemer remembers days like this. He began picking and shelling corn when he was only ten. First he walked through the fields with his dad and brother, snapping ripe ears from corn stalks while removing husks at the same time. As they threw the ears over their shoulder, they aimed for bang boards set up high on one side of the wagon. The boards kept the corn from being thrown over the top, dropping instead into the wagon box below.

On a good day in a good year a person could hand pick 100 bushels, Schutte said, loads which horses hauled into the farm place to be unloaded into a ventilated and slatted corncrib or a ring. Corn in a ring was piled onto a concrete or wooden platform, encircled by picket fence tied with wire and piled three deep. Eventually, hand-picking was replaced with two-row, pull-type, mechanical corn pickers.

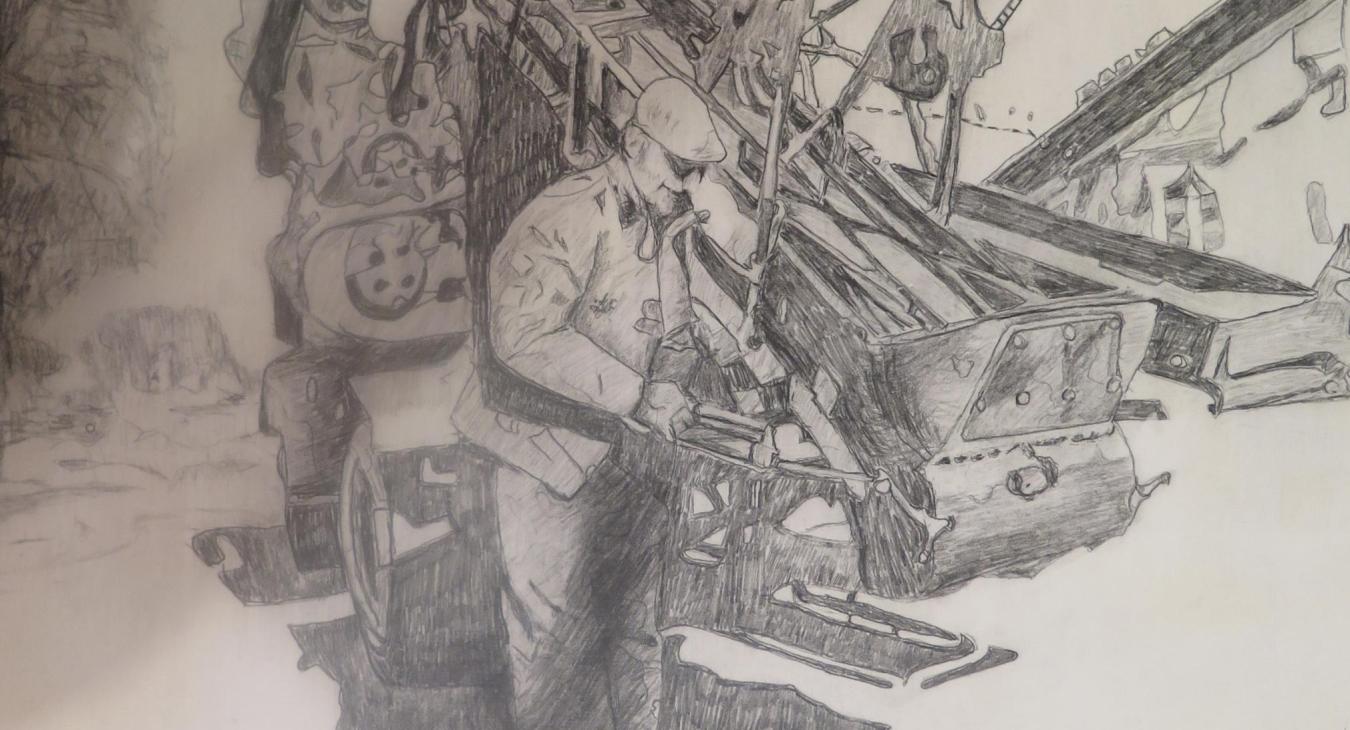

When the day for shelling was selected, the man running the corn sheller was summoned, by telephone if the farms had phone lines by then, along with several neighbors to help. They used corn rakes to loosen up and tumble the corn down from the sides of the pile where it had settled in tight. They placed the end of an elevator or conveyor—a drag feeder—under the alley in the corn crib or pulled out a few wire tunnels from beneath the corn in the corn ring, and began scooping. The wire tunnels were removed as they went, making room for the drag feeder into which corn was scooped and conveyed into the sheller on the back of a truck. At the end of the day the shelled corn was again scooped, this time from a wagon into a granary, hopefully free from mice and rats, where it was eventually scooped out once again and fed to the livestock.

Usually, a ring was filled with 1,200 bushels of ear corn, a good morning’s work, Schutte said. Pay for the shelling crew was a tasty lunch or dinner. If a neighbor didn’t do his share of the work, you “looked the other way,” he said.

In later years, a loader mounted on a farm tractor did the scooping. “That took a lot of labor out of running the sheller,” Schutte said, if it didn’t scoop up too much dirt in the process.

Tom Brockman of Norfolk, Nebraska, remembers those days as well. His father, Pat, farmed, worked as a hired man, followed the wheat harvest, and assisted in a shelling operation. In 1945, he moved his family to Pilger, Nebraska, where he purchased his own sheller. Situated on the back of a Diamond T or a Max Thermodine straight truck, the sheller’s cylinders stripped the kernels from the ear and sorted them via a series of sieves at a cost of three cents a bushel.

“My dad was pretty doggone inventive,” Tom said about his father. Pat worked with a machinist to build a rack to cart the conveyor from farm to farm on the side of his truck. The conveyor—through the utilization of a custom-made, split drive shaft and pulley system—could be winched into place at the corn pile with the yank of a bar in the truck cab, without having to unload and attach each piece of the conveyor by hand.

Once the corn was delivered to the sheller, a blower sent the empty husks one direction, the cobs in another, and the shelled corn in still another.

Typically jobs were small, but sometimes the Brockman sheller ran all day. Tom’s dad also ran it fast. Tom remembers one day when they shelled several rings of corn, weighing in at the local farmers cooperative where the scales showing they had shelled 1,000 bushels an hour.

Pat Brockman kept at it through the late 1970s. Some farmers by then had quit picking corn in the ear, replacing the two-step picking and shelling process with a self-propelled combine which ran through the fields, picking and shelling corn as it went. When Pat Brockman decided to quit the business, corn shellers sold for little or nothing, Tom said.

Today, the corn sheller and two-row picker have been replaced with super-sized combines; its tires alone are taller than a corn picker used to be. Sixteen-row cornheads and a modern-day machine can combine as much as 7,200 bushels an hour.

What its operators are missing, however, is the exercise found on the working end of scoop shovel and the neighborliness accompanying visits over mid-morning lunch break on days the sheller came to the farm.